Your Cart is Empty

The kimberley Process Certificate

how conflict free diamonds can still be blood diamonds

TLDR

The Kimberley Process isn’t your get-out-of-guilt-free card for diamonds. It doesn’t touch state violence (think: Russian-Ukraine war, the Gaza conflict), skips right past child labor and environmental harm, and only certifies rough diamonds at the border. Not the hands that mined them, not the rivers turned brown, not the journey from pit to ring. Mix in some creative parcel swapping and cross border loopholes, and you get a diamond industry where even “certified” stones can fund war, line a dictator’s pocket or end up in your engagement ring right next to your grandma’s banana bread recipe.

The Kimberly Process Certification Scheme (KPCS) isn't keeping all the blood diamonds out of your engagement ring.

If a jeweler tells you otherwise (or tells you that because the KPCS is in place, you're guaranteed the diamonds in your diamond ring are conflict free) run away. Shop elsewhere.

Ethical sourcing is a term so many businesses are tossing around these days. But it isn't a hashtag or a label. There aren’t easy answers or quick fixes to solve the problems facing us today. While the diamond industry has taken action towards addressing some of the shortcomings in bringing stones to market, there's still work to do.

The first step to ethical sourcing is to establish verifiable origin. Once we know where a diamond came from, we can begin to address labor practices and environmental sustainability. The more consumers are requesting details around origin, the louder the cumulative demand for it will become within the industry. If we’re going to push the needle forward and raise the standards in our industry, it’s going to take all of us engaging in the ongoing ethical sourcing conversation. It's going to take all of us asking questions.

Let's start with these.

So what's the Kimberley Process?

What is the Kimberley Process?

The Kimberley Process Certificate Scheme (KPCS) is basically a handshake between governments, cooked up to clean up the diamond industry’s reputation after the blood diamond scandals hit the headlines. The original pitch? Only trade rough diamonds from “non-conflict” countries, so everyone can sleep better at night thinking their diamond is squeaky clean.

Fast forward to now, and the Kimberley Process likes to boast it blocks 99.8% of conflict diamonds from the global supply chain. That number is all about who’s in the club, not how well the system actually works (spoiler: there are plenty of loopholes big enough to drive a diamond mine through).

The goal was simple: stop rebels from trading diamonds to fund wars by making countries jump through some paperwork hoops before they can export rough stones. If a shipment ticks the right boxes, it gets a Kimberley certificate saying those diamonds are conflict free. In theory, that’s meant to keep the bad stuff out. In practice, it certifies parcels, not people, and definitely not clean hands all the way down the supply chain.

What it does: require KP certificates on cross border shipments of rough diamonds.

What it doesn’t do: cover polished diamonds, guarantee humane mining conditions or address state violence, forced labor or environmental harm.

Even experts can't tell whether a diamond is conflict free or not just by looking at it.

Who is Kimberley?

The Kimberley Process Certificate Scheme (KPCS) isn’t set up by a female hero with the transformative act to uplift diamond supply chains from their deadly past. Kimberley refers to the South African city where the KPCS first began. Kimberley comes from the word kimberlite, a type of igneous rock that sometimes contains diamonds. The city Kimberley is home to one of the first industrial level diamond mining endeavors, and that’s how it got its name.

Errr rebel groups? What do diamonds have to do with rebels?

In short, everything. Diamond mining in Africa was at times controlled by rebel groups for money laundering and terrorist financing. They would gain control of local mining areas and use the profit to finance salaries and the purchase of weapons to oppose the government. Even if they don’t control the mines themselves, rebel groups may act as middlemen for artisanal and small scale miners selling rough diamonds in mining areas.

Sometimes the government was involved, facilitating access to terrorist groups like al Qaeda in exchange for diamonds and weapons.

Human rights groups learned about the funding system of various rebel groups in Africa, acknowledging diamonds were at the source. Hence: blood diamonds.

What has the Kimberley Process achieved so far?

The KPCS has been able to decrease conflict diamonds from an estimated 4% of world trade to less than 1%. In this sense, the KPCS has really limited the use of rough diamonds to finance war.

The KPCS itself hasn’t contributed to humanitarian disaster as traditional sanctions often do. In fact, supporters of the KPCS have been careful to provide the means to mitigate any negative impact on the small scale miners relying on diamond sales for their livelihood.

How does it work?

The KPCS was enacted by the United Nations in 2003. The KPCS works by enforcing participating governments to meet their minimum requirements, which include things like ensuring that rough diamonds are imported and exported in tamper resistant containers and establishing a system of internal control to eliminate conflict diamonds imported and exported into the territory.

Many of these things, as you can see, means the government has to self regulate themselves. And that comes with a lot of problems.

Diamonds are often traded in mixed-origin parcel, practically removing traces of its source.

How are NGOs involved in the Kimberley Process?

In the early 2000s, NGOs played a significant part in raising awareness about conflict diamonds. The NGO Global Witness was one of the first organizations who brought the issue of conflict diamonds and war diamonds to international attention with their report A Rough Trade. This report inspired the film Blood Diamond. It was pressure from NGOs and consumers that pushed governments and the diamond industry to take action.

Even though the NGOs can participate in all official meetings of the Kimberley Process, they don’t have the right to vote. Their observer status means they have zero direct decision making power in the Kimberley Process.

Most of the NGOs that were initially included in the Civil Society Coalition in 2007 have left the initiative. Global Witness issued a statement declaring that, “nearly nine years after the Kimberley Process was launched, the sad truth is that most consumers still cannot be sure where their diamonds come from, nor whether they are financing armed violence or abusive regimes.”

NGOs that have left believe the Kimberley Process failed to address human rights abuses associated with the diamond trade. They worried the initiative didn’t credibly address the protection of local NGOs monitoring and reporting to the Kimberley Process on field and on-site conditions, basically preventing NGOs to act as a moral guardian and watchdog.

Even though the NGOs can participate in all official meetings of the Kimberley Process, they don’t have the right to vote.

Why does it not work?

Remember that Africa is a giant continent with many countries within, and diamonds are both very small and very valuable. Connected by land, precious goods can be smuggled through borders and passed on as “ethical”.

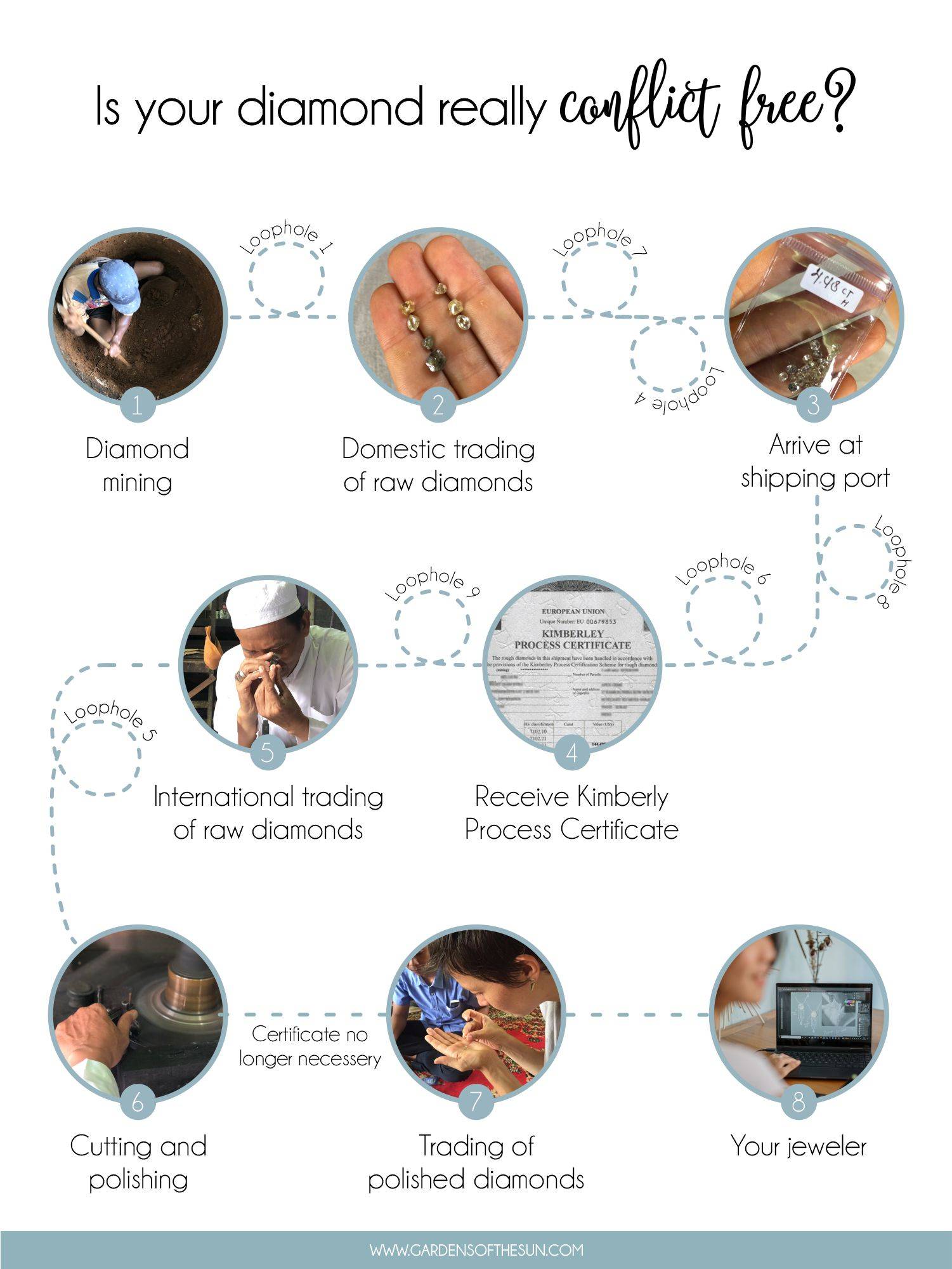

The Kimberley Process Certificate doesn’t apply to the initial extraction process. The certification doesn’t begin at the mining site, where most atrocities happen. It doesn’t offer reassurance that the mining was legal or that no human rights were abused at the mine site or anything about the environmental impact. It’s simply a label given at a port for a batch of goods about to leave the country. It just cares which country the rough diamonds are exported from. Whether that includes rough diamonds that travelled through multiple countries, no one can tell.

Under the KPCS, diamonds can be smuggled from one country to the next, where they may be certified as conflict free even when they’re not. This has been happening on a large scale with billions of dollars worth of diamonds.

Since the certification applies to batches of diamonds, traders mix diamonds from multiple mines into a single shipment. Anyone with bad intentions can remove the trace of a diamond’s bloody past by mixing it in with diamonds from legitimate sources, or exporting it from a country in good standing with the KPCS. Once the blood diamond is shipped off with a Kimberley Process Certificate, a rebel group somewhere can continue their atrocities.

Another way to bypass the KPCS entirely is by mixing it together with other diamonds when they’re being cut and polished. This is because once a raw diamond has been polished, there’s no way of telling a good diamond apart from the bad.

There are

MAJOR LOOPHOLES

in the Kimberley Process Certificate Scheme (KPCS):

LOOPHOLE 1:

So many hands

Diamond industry experts like to say a packet of diamonds will change hands on average eight to 10 times between the country of export and its final destination. The reality is that diamonds from artisanal miners are likely to change hands just as many times before they even arrive in the capital to be certified for export.

This makes it near impossible to trace diamonds to their source in countries where artisanal mining predominates. Jewelers who want a more transparent supply chain usually end up buying from large scale mining companies like De Beers or Rio Tinto, which control all aspects of the process from exploration to cutting and selling.

Diamonds from artisanal miners are likely to change hands eight to 10 times before they even arrive in the capital to be certified for export.

Loophole 2:

You can’t readily tell where a diamond is from

Alluvial diamond mining in South Kalimantan, Borneo island, Indonesia

Even experts can’t tell the origins of a diamond simply by looking at it. An experienced gemologist might be able to tell the difference between a handful of rough diamonds from an industrial Russian pit mine and those from an Indonesian alluvial deposit. But once a diamond is cut, there’s no scientific or technical way to tell where that diamond was mined. Laundering a conflict diamond from a place like the Central African Republic is as simple as cutting it.

Loophole 3:

Only against rebels

The Kimberley Process has managed to decrease the estimated circulation of conflict diamonds from 4% to 1%

The KPCS focuses on the narrow definition of conflict diamonds as “rough diamonds which are used by rebel movements to finance their military activities, including attempts to undermine or overthrow legitimate Governments”, leaving broader issues like human rights violations, poor working conditions, unfair pay, child labor and environmental impact unaddressed. Even though rebel groups are the core issue addressed by the KPCS, underlying issues like environmental degradation, poverty and bad governance can give rise to conditions for more rebel groups, and so the cycle continues.

That said, the KPCS is a lazy way to tackle a very complex problem. Even though the mining and distribution is legal, it doesn’t mean that the diamonds are ethical. Those controlling the State and corporate actors can be just as abusive, just as corrupt in maintaining power and also use diamond revenue to fund politics or human rights abuses. It does not address issues of poverty and exploitation, or how human right abuses tend to be interlinked. Diamonds involved in conflict and human suffering can still enter global supply chains.

Laundering a conflict diamond from a place like the Central African Republic is as simple as cutting it.

One example is the treatment of diamonds from Zimbabwe. Government forces seized control of the Marange diamond fields in eastern Zimbabwe. More than 200 miners were murdered, thousands more were raped, injured and enslaved. Since the KPCS defines conflict diamonds as coming from rebel-controlled territory, and there were no rebels, the Kimberley Process didn’t call diamonds from that area conflict diamonds. Governments causing conflict themselves aren't addressed.

The KPCS certifies that a parcel of diamonds most likely didn’t fund rebel movements. It’s a very narrow scope, similar to that a FairTrade product isn’t necessarily organic. Certification schemes like B Corp exist that certify an entire business and how it operates, tackling wider issues than only fair pay or how a product is grown. For diamonds, the scope is still narrow.

LOOPHOLE 4:

Only applies to rough diamonds

It's a rare chance to check diamonds at its source - so I lept at it!

After a rough diamond is mined and extracted from the earth, it’s cut, then polished and then often resold on the market. Only the first part of the supply chain is subject to the requirements imposed by the Kimberley Process.

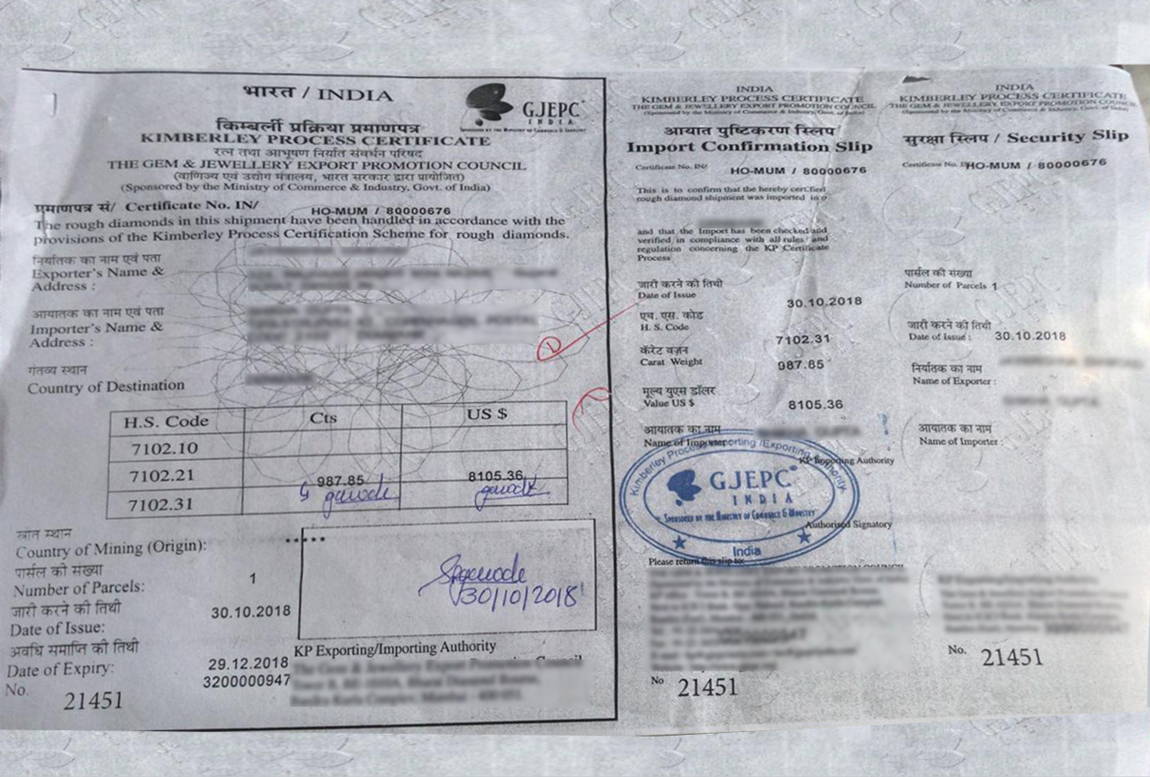

Cutting and polishing has shifted from mainly Belgium, Israel and the US, to India and China. Only the rarest and most precious diamonds are still worked in Antwerp, rather than in Asia, because of local expertise and quality control. India’s role in the global diamond industry is irreplaceable, accounting for 80% of the carat weight and 60% of the value of all of the world’s diamonds.

As the world’s major diamond cutter and polisher, most diamonds make a trip to India at some point in their journey. Once diamonds are brought to the Indian market, their origin is difficult to trace. Rough diamonds travel in and out of the country and are traded within the country like at a vegetable market, often split into smaller and smaller parcels to accommodate smaller traders and cutters. Conflict diamonds can be mixed into these smaller parcels of conflict free diamonds, each smaller parcel holding only a copy of the original certificate that accompanied the diamonds when imported. Once the rough is polished, the weight will be much less than the rough diamond weight and it’s nearly impossible to know if they were indeed imported in the said parcel.

Rough diamonds are traded like at a vegetable market, often split into smaller and smaller parcels to accommodate smaller traders and cutters.

Even though India enforces the Kimberley Process, you can imagine how hard it is to exercise strict monitoring. Illicit diamonds can be smuggled directly into a polishing factory. Once polished they no longer fall under the oversight of the Kimberley Process, since certificates no longer apply to polished diamonds.

If the KPCS were to include the cutting and polishing of diamonds in its scope, it would add an additional price tag to already expensive diamonds. Each diamond sold on the market would need to have two additional levels of certification on top of the extraction of the diamond: the cutting and the polishing of the diamond. That process would cost money, at least in the short term, to implement all the required mechanisms to certify cut and polished diamonds. In 2012, the US as that year’s Chair of the Kimberley Process proposed broadening the scope to include cutting and polishing centers. However, some countries, including Russia and Zimbabwe, blocked the proposal.

LOOPHOLE 5:

Mixed origin parcels

In reality, even though these diamonds come from the same mine, they'd be traded in different parcels, according to their color and size.

Oddly enough, the KPCS allows certification for mixed origin parcels. Of course the assumption is that those diamonds in the parcel will be conflict free, but we know this isn’t necessarily the case. Mixed origin parcels happen because diamonds are often graded first by color, clarity and weight, before origin. So you can have diamonds of similar quality (say, salt and pepper diamond parcel or yellow diamond parcel), but from different mines or countries or even continents, in a single parcel. The parcel could then be labeled as “Botswana and Russia” or even “mixed origin.”

Diamonds are graded by color, clarity and weight, before origin. So you can have diamonds of similar quality (say, salt and pepper diamond parcel or yellow diamond parcel), but from different mines or countries or even continents, in a single parcel.

Countries like the United Arab Emirates (which doesn’t produce diamonds) are allowed to trade internationally and can legitimately label the diamonds they export as Kimberley certified, even if genuinely conflict free diamonds were mixed with diamonds smuggled from, say, Angola or Ivory Coast *sigh*. Since the United Arab Emirates can trade mixed diamonds, they’re in another way ‘permitted’ to remove the origin of those diamonds. Few diamond companies do this, but it takes only a few bad actors.

Loophole 6:

False certificates

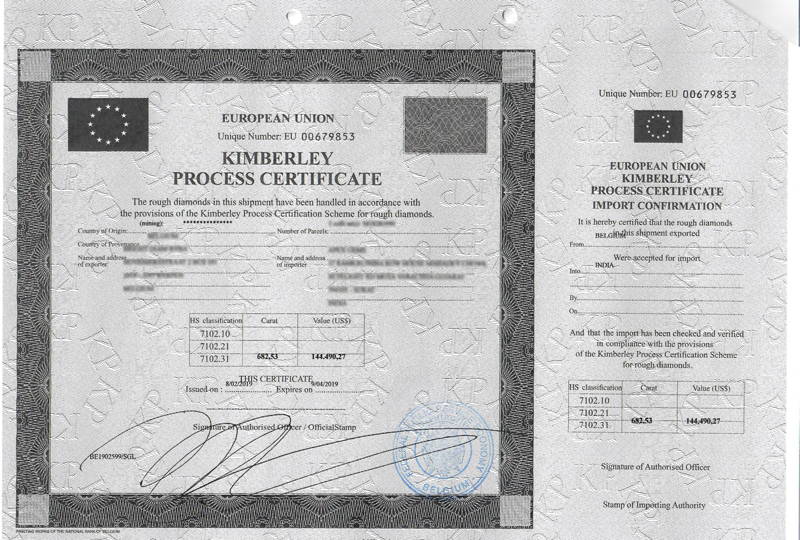

Lack of standardization in how the certificate is issued

Each country is responsible for issuing the certificates, and the lack of harmonization means not all certificates are equally valid and relevant. Most of them, including the certificates issued by the European Union, are printed by security printing firms and have a tear-off section to be returned to the sender for confirmation of receipt. However, some countries issue certificates that are more basic.

For example, the United States uses a barcode instead of a security printing code, displaying only basic information (the exporter, the importer, the date of issue, the date of expiry, the number of parcels, the carat weight/mass, and the value in US$), and doesn’t have a tear-off section.

The lack of harmonization makes it more difficult to identify fake certificates. The KPCS doesn’t resolve the issue of smuggling, and makes room for a new form of criminal activity: fraudulent Kimberley Process certificates. While smuggled rough diamonds and fraudulent certificates may present only a fraction of the global trade in rough diamonds, they undermine the process as a whole.

Loophole 7:

It’s voluntary

Because the KPCS is voluntary, it’s like a form of soft law without coercive enforcement. The stick is being kicked out of the Kimberley Process and the loss of a market to sell the diamonds legally.

Strong monitoring and enforcement includes third party audits, public disclosure of the results, and the imposing of sanctions (like being expelled) on those who don’t meet the standards.

The KPCS doesn’t resolve the issue of smuggling, and makes room for a new form of criminal activity: fraudulent Kimberley Process certificates.

LOOPHOLE 8:

Lack of third party verification

A miner checks the quality of the diamonds he mined

Plenty of evidence exists of diamonds from conflict zones being smuggled into neighboring countries, where they enter legal channels and are then exported as with a KPCS certificate. Most conflict diamonds come from alluvial or artisanal mining. These are much more difficult to monitor than large-scale industrial mining.

The entire premise of the KPCS is built on statements made by the government - a seal on the parcel. These don’t need to be verified by an independent third party. Just like the blood diamonds themselves, there’s no way of telling whether the statement tells the truth. NGOs can have a role as watchdogs and help monitor the system. But since most established international NGOs have left over the years, and have been replaced with younger, national-level NGOs with less experience in conflict diamonds and fewer financial resources, their role in monitoring is diminished.

Most established certification schemes, like the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) and the Rainforest Alliance have systems for monitoring and third party verification. Although the lack of independent, third party verification means the cost of compliance stays low, it essentially weakens enforcement of the KPCS.

Loophole 9:

Tax evasion

Alright - so diamonds move from one country to another in its enormously long trading process. You’re probably familiar with this by now. Here’s the real news: for every transit, the company has to issue a new invoice, and that invoice often doesn’t reflect the real value of the diamonds. Multiple companies (oftentimes they’re offshore, located in tax haven countries like UAE, and owned by powerful, greedy autocrats) basically make up the value of diamonds so that they can evade tax and earn extra profit somewhere else.

Since the KPCS has little to do with the pricing of those diamonds, yet is powerful enough to allow certain countries to move diamonds around under its scheme, there’s room for corruption. Dirty financial gains still occur under the Kimberley Process umbrella, somewhat protected by its own mechanisms. Imagine if the same people put the same amount of effort into cleaning up their act.

Conflict free diamonds

The verdict

So now you know how blood diamonds can still end up in your engagement ring.

Although the KPCS has significantly reduced the amount of conflict diamonds ending up in jewelry, it fails to address many important questions:

Like: where exactly did the diamonds come from? What is the environmental impact involved in extracting these diamonds from the earth? What are the labour conditions, wages and practices employed in the mines where these diamonds were unearthed?

Diamonds from known origin

A solution?

We love working with suppliers with similar values. People who believe responsible sourcing starts with knowing the origin of your diamonds.

Ashkan Asgari fromMisfit Diamonds explains this: "For me the first step towards tackling the issue has been that of establishing documented, verifiable origin. Once we know where our diamonds came from, we can begin to address labor practices and environmental sustainability."

A selection of our diamonds come with certificate of origin, specifically those from Australia and Canada. We sourced these diamonds from Misfit Diamonds. Why these countries? "Mines in Canada go through rigorous assessment processes to ensure that the environmental impact of the mining is minimal and that the mines can be returned to their natural state once they go offline. The labor practices and conditions employed in the extraction of these diamonds from the earth set the standard for what diamond sourcing can and should look like within our industry."

We also source diamonds from Indonesia. Officially, Indonesia doesn't produce any diamonds. But how about the rubber farmer who finds diamonds in the soil underneath his rubber plantation? How about the hundreds of artisanal diamond miners? There are no Kimberley Process Certificates for these diamonds. They may not be exported as rough. But once polished in the country, these diamonds meet the criteria of being conflict free. Moreover, we believe these diamonds do not violate human rights, and that the miners receive a fair price for them.

There are also countries that participate in the KPCS that we refuse to source from. For example:

Ivory Coast - human right violations and armed conflict

Sierra Leone - human right abuses and armed conflict

Angola - lack of transparency, child and forced labor, human right abuses

Zimbabwe - human rights abuses

Democratic Republic of Congo - armed conflict and lack of transparency

Israel - funding the Gaza conflict

Russia - funding the war on Ukraine

So let's keep asking the hard questions. Let's keep asking where our diamonds came from. And let's keep working towards more ethical sourcing of the diamonds, gemstones and precious metals that make up your jewelry.